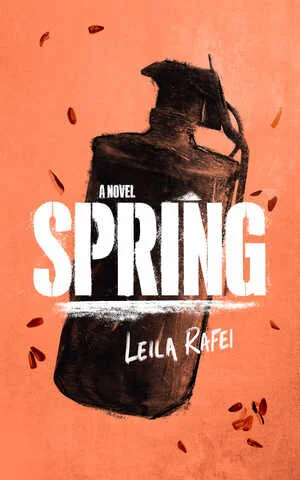

A Review of Leila Rafei’s Spring

By Lauren D. Woods

The Cairo of Leila Rafei’s Spring is a medley of dust and smog, crowds, and painfully beautiful moments. It is alternately the Cairo that one of Rafei’s three main characters, middle-aged, provincial Suad, understands as “the big city where the streets stank of beer and hashish, and foreigners ran around half-naked with hair flapping in the wind, legs wide open to every tea boy and taxi driver in sight.” It is the home Jamila, a Sudanese refugee, knows, “where the city crumbled into slums, where sand took the place of asphalt, and only tuk-tuks could pass.” And at times, it is the Cairo that Sami, a young college student studying petrochemistry, sees with “the kind of beauty with flaws like dust and wear and cacophonous sound, flaws that somehow made every speck of prettiness even prettier, like Umm Kalthoum singing over bleating car horns and bougainvillea buds glimmering against walls caked in grime.”

Spring is Leila Rafei’s debut novel. The author grew up in the Washington, DC area and now lives in New York. She has a Master’s degree in Middle East Studies from the American University in Cairo, where she lived for two years during the Arab Spring. Rafei writes for the American Civil Liberties Union and has also worked for the World Bank.

With sparkling prose and deeply built characters, Rafei tells the story of Egypt’s 2011 revolution from three alternating perspectives. There is Sami, who’d rather get tossed into a police truck and hauled off to Tora Prison than have word get back to his mother about his American girlfriend. Suad, Sami’s traditional mother in Mahalla—a Nile Delta city known for its textiles—whiles away her days weeding her lemon grove and willing her children to embrace the traditions she did, even though those same traditions landed her an unfulfilling life. And finally, Jamila, a pregnant Sudanese refugee, searches for her missing husband and tries to build her resettlement case to leave Egypt for a new life.

This story wouldn’t have worked if Rafei had tried to tell it from just one perspective. It’s through this array of characters that she captures the range of reactions and emotions throughout Egypt to the revolution that bubbled up in 2011 after Tunisia revolted first in December 2010, Egyptian police brutally killed a young Egyptian man in an Alexandria café, and in January 2011 Egyptians across the country decided three decades of authoritarian rule under then-President Hosni Mubarak were enough and turned to the streets.

The novel brought me back to my own experience of living in Cairo in 2011, working for the U.S. Embassy, and trying to make sense of these extraordinary events. The descriptions of expat life, with circles generally limited to neighborhoods like Zamalek, felt very real. And the decision by Sami’s girlfriend, Rose, to leave the expat life there for a neighborhood with “real Egyptians” felt familiar, as did moments when Rose faced the limits of how much she can truly understand as an American. Even little details—like the stench of burning rubber at checkpoints throughout the city—all came back to me with this read.

There are 18 chapters in the novel, one for every day of the revolution. As the revolution proceeds, each character is drawn deeper into his or her personal crisis—Sami hiding a secret life, Suad wanting Sami to get in touch with her and back on track as a good son, and Jamila, who wants to find her husband and take refuge in America. The growing revolution complicates the journey for each.

Throughout the book, Rafei’s ability to take us through the complex politics of Egypt’s revolutionary period is remarkable. She’s able to shed light on political and social dynamics, from the wealthy clients whose homes Jamila cleans to her poorest neighbors, from the Mubarak supporters to the revolutionaries.

There was a moment near the end where I actually fell in love with this book. Shortly after a powerful event in Jamila’s life, there’s a quiet moment in Cairo, with the sound of a distant muezzin calling Cairo’s Muslims to prayer. In one sweep, Rafei depicts the slums and the catcalls and the minarets and the solidarity of Egyptians and beautiful moments in Cairo. She captures so effectively the love-hate relationship of so many who live there, this city full of contradictions and conflicting stories and viewpoints, all strung together in some form that somehow, against all odds, keeps going. And she accomplishes it with honesty, without condescension, in a manner that feels fair.

There is one more thing I should note about Rafei’s book that is woven in with such subtlety I don’t know whether it was intentional or not, but it’s important—perhaps the most important aspect of the book. It’s the fact that a political revolution doesn’t necessarily bring about a social or personal one. Some very important and unexpected things shift in the characters’ lives, while others stay the same. The real and deepest forces in people's lives, after all, are not just political. They’re traditions, expectations, the way we relate to people around us, and they don’t move as easily as the shifting political winds. Those rooted traditions—the ones you can’t change—lead Spring to an ending I found a little unsatisfying. Yet, I can’t think of another way to end the book because it’s true to the characters and real life.

And perhaps my dissatisfaction there is an extension of the deeply unsatisfying trajectory of Egypt’s real revolution. January 2021 will mark 10 years after the events Rafei writes about, but still today, Egypt’s Army remains in power, with citizens disenfranchised and activists in prison, the same repressive government with new faces. It’s a reality reflected across the region. Syria and Libya have collapsed into conflict, Yemen has faced foreign proxy wars, and the region is far from achieving peaceful democratic change. Even beyond North Africa and the Middle East, political freedoms and civil liberties are backsliding worldwide. Although Rafei’s characters—Sami, Suad, and Jamila—live in Egypt, the political barriers they face are shared by many around the world. Spring is a perfect novel to reflect on those realities and consider how much of the world has changed since the Arab Spring, and in the end, how much hasn’t.

Lauren Woods is a DC-area based writer. Her fiction, essays, and reviews have appeared in journals including The Antioch Review, Wasafiri, The Offing, The Washington Post, and others.

https://www.onbuy.com/gb/?extra=dctrending